Now you may ask, what’s the difference between these three settings? But delivering the meal no longer requires all that overhead, all we need at the table is that one plate with the finished product on it, that will not be altered any further (except maybe with a little salt and pepper).In Photoshop, you can set your photo or project to 8-bit, 16-bit, or 32-bit. Preparing the meal properly actually requires a much larger work surface, more ingredients (like it needed half an onion, but the store will only sell you a whole one), and a lot of water, energy, and a range of tools. But the meal could not have been prepared only with the plate and the space on it. What we eat is a plate of food, and that’s exactly what we expect.

#CONVERT 16 BIT TO 8 BIT PHOTOSHOP MOVIE#

But the rendered digital files delivered at the movie theater or on your home AV system do not match the file size, bit depth, and quality level of the original media files (stacks of tracks and clips) that were put together to create the final movie or song. The digital files that you listen to or watch sound and look great. This works the same way with the digital music and movies you enjoy. What can be reproduced in print is typically reproducible at 8bpc, again if no additional major edits will be made. The copy sent to a print shop can be flattened, 8bpc, and even JPEG (if high quality), and the final print will look good, because the penalties for stepping down the specs don’t happen if the print shop makes no further major changes to that file.Īnother reason is that a print can only reproduce a smaller dynamic range and color gamut compared to the original file and on-screen editing, so print can’t reproduce it all anyway. You can just keep the final results, and drop much of the rest. The tonal resolution of 16bpc helps prevent the banding that large changes might create.īut when you are done with changes, it is much less necessary to preserve all of the overhead.

#CONVERT 16 BIT TO 8 BIT PHOTOSHOP FULL#

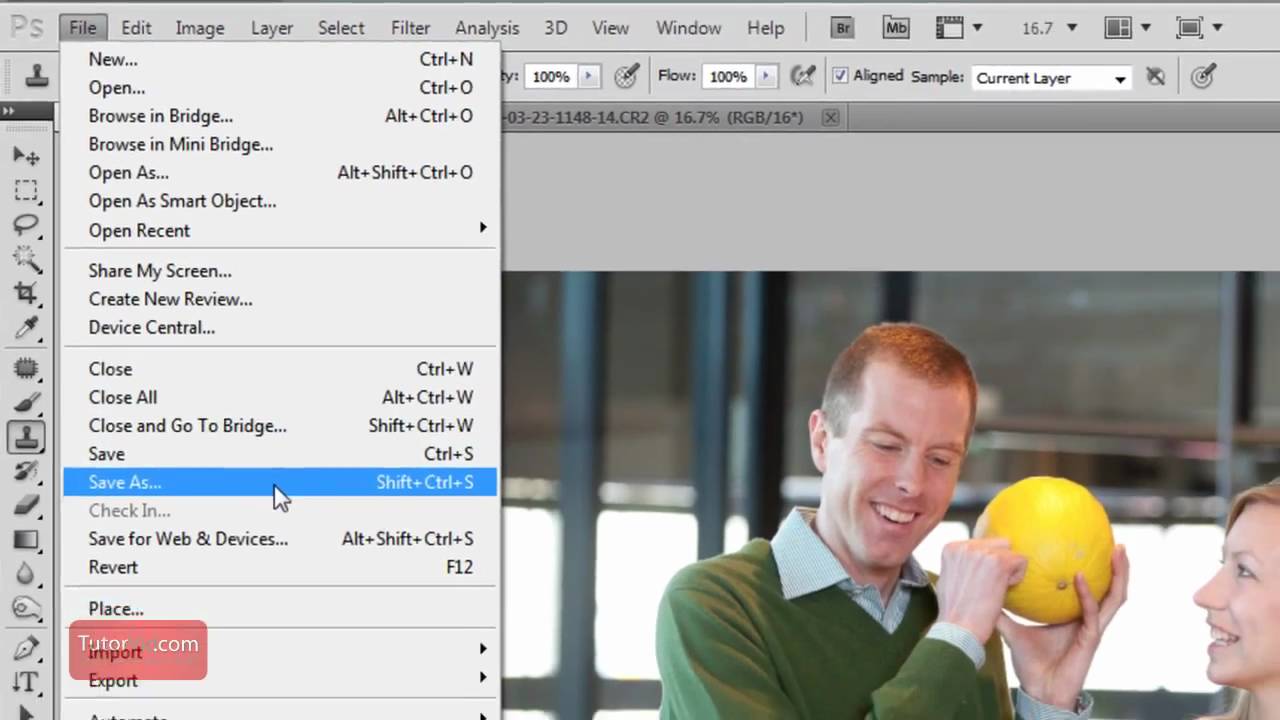

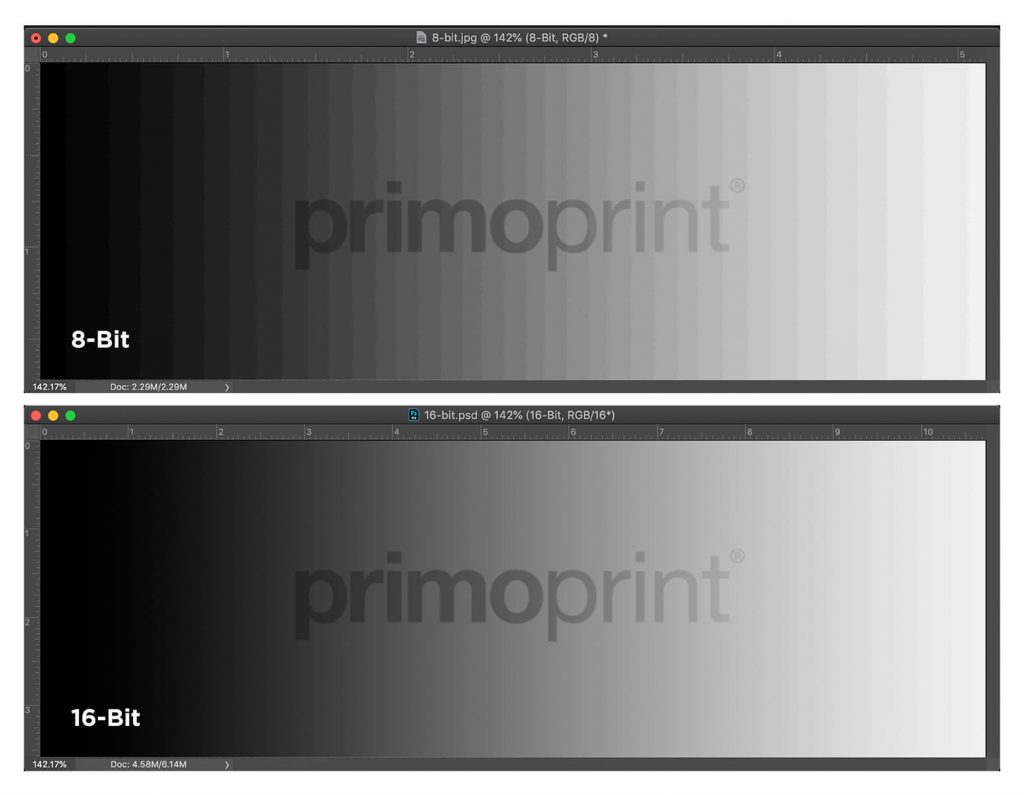

16 bits per channel (and similarly, the full original color gamut), gives you the resolution and room to maintain quality as you make change after change. In editing, you need maximum flexibility, overhead, resolution, and margins to make changes, whether that’s redistributing the tones, preserving highly saturated colors, or making local adjustments. It’s the difference between the requirements for editing, and the much simpler requirements for final delivery. Can anyone explain that or point me in the direction of an article that does explain it? But I have no clue why 8-bit editing is problematic but conversion from a 16-bit to an 8-bit file does not seem to result in a degradation of the image. It seems like it makes sense to edit in 16 bits even if the file needs to be converted to 8 bits for printing. I found no banding in areas that included gradual color transition and a barely perceptable difference in color limited to highlights. As an experiment, I made a copy of a 16-bit file, converted it to 8-bit, then compared the 8-bit side-by-side to the 16-bit original at print view (in this case, 22"x40"). gradients or mist over a field) where there is obvious banding in the 8-bit file.

I've seen an obvious advantage in 16-bit rather than 8-bit editing, especially with respect to very gradual color transitions (e.g. I was surprised to find that photo labs with a reputation for high quality fine art printing (e.g., Bay Photo or Whitewall) request 8-bit images. I've only recently become interested in printing my images.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)